I found this old essay in a folder on my computer. I wrote it a couple years ago when I was working in a museum, but then I quit that job before I did anything with that essay. I still relate to what I had to say in the essay, so I decided to toss it up here:

When you work in the galleries of a museum, you develop relationships with certain images. While it is true that the curators select the images, they soon abandon them. It is left to those of us who work in the galleries on a daily basis – tour guides, security guards, etc. – to justify, explain, physically protect, and live with the framed images. The images that you develop the strongest connection to are often not the ones that grab you at first, but the ones that grow on you gradually. A simple gesture or expression takes on greater meaning once you view it hundreds of times over.

I developed one such relationship with a Bruce Davidson image this past summer, during ICP’s A Short History of Photography exhibition. The image – from Davidson's Brooklyn Gang series – is of a young woman standing in a park, with a cigarette in her mouth. She is wearing a white, sleeveless blouse and a black skirt. Her bare arm is pulled back at a severe angle. At first glance, I thought the girl was pulling back to strike – the harsh look on her face would support this – but she's actually just fixing her hair, which has been disrupted by the wind.

The picture is messy. The girl is in the foreground, but she is firmly planted in the right half of the horizontal frame. Poking into the left half of the frame are a couple of the girl’s friends, napping on a white blanket. Above them, an overturned bag lies on the grass. Even if Davidson had cropped off the left side, the portrait of the girl would still include the khaki-panted leg of a stranger trudging along a path in the background. Beyond the legs, there is a wall of bushes, dark and enclosing. The ground is uneven, and the grass looks unhealthy. The girl is not well either. She looked very tough at that first glance, but the more I looked at the photo, the more vulnerable – and younger – she appeared.

After the show was taken down, I wanted to revisit the photo in its context. Davidson spent the summer of 1959 following the Jokers, a crew of poor, mostly Irish, kids from the vicinity of 18th Street and 8th Avenue, a dismal corner of pre-gentrified (by decades) Park Slope. The kids are certainly delinquents, they steal cars to joyride and fight rivals with baseball bats, but they are not quite what would be considered a violent street gang by the standards of later decades. Brooklyn Gang originally ran as a spread in Esquire Magazine in 1959, but the entire series was only published as a monograph in 1998, by Twin Palms Publishers. The monograph has been reprinted this year by Steidl as part of Black & White, a beautiful five-volume boxed set of Davidson’s black and white works.

Brooklyn Gang is divided into nine sections, set in the various places where the kids spend time. There is “Candy Store,” where they read comic books and drink fountain sodas, “Party,” where they dance slow and make out, “The Street,” where they work on cars and smoke cigarettes, “The Hole” (a sort of submerged alley running alongside an apartment building), where they smoke cigarettes and drink. The photo of the girl is from the “The Park” section. Park Slope is defined by the fact that it leads up to the West side of Prospect Park, and it was natural that the Jokers hung out there.

Prospect Park was built by Frederick Law Olmstead and Calvert Vaux in 1867, following a rough draft called Central Park, and is one of the most beautiful parks in the world. It is a place where friends and families gather for recreation, but it has often been a place of violence as well. In fact, the location for the park was chosen largely because of the desire to preserve Battle Pass, a site where American troops tried, and failed, to hold off invading British troops during the Battle of Brooklyn in 1776. There were battles there in 1959, too. Davidson initially came down and met the Jokers after hearing about a violent brawl between teen gangs in the park.

One of the ways that the Jokers manifested their tribalism was through tattoos. Indeed, tattoos are a central aspect of the book's visual lexicon. They are not only present, but proudly displayed, in many of the images in the book. The tattoos are all fairly rudimentary: the words “Mom” and “Dad,” the nickname “Bobby” surrounded by stars, drawings of panthers, eagles, flowers, and skunks, all chosen from standard flash sheets.

I remember the single tattoo that adorned the forearm of my uncle, a tough fifties kids himself. It was a Marine Corps bulldog, which he got during the Vietnam War. A flash tattoo will not have the same individuality, or sensitivity to body contour, that we seen in custom tattoo work done in Brooklyn today. My uncle’s tattoo was awkwardly placed and poorly done. Still, it remains one of the most powerful tattoos I have ever seen, as it meant that he had been part of a tribe, and had ventured into battle with his brothers. The Jokers’ tattoos meant much the same thing.

Most of the Jokers got their tattoos done at Mikey’s Tattooing in Coney Island. Following a hepatitis outbreak in 1961, all tattoo shops in New York City – including, no doubt, Mikey’s – were closed by the city. By the time tattooing was legalized in New York City again, in 1997, tattoos were no longer the sole province of sailors, bikers, and gang members. Nor, for that matter, was Park Slope any longer the province of the poor and working classes.

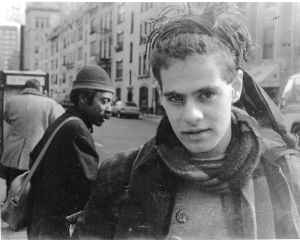

Recently, I have seen some of the “Brooklyn Gang” photos kicking around on the internet. Often, the interest is in the retro cool quality of the pictures. I admit that I am as susceptible to this as anyone. The tattoos are cool, the clothes are cool, the perfectly combed hair is cool. The book is full of attractive teenagers making out. Beyond that, there is a something charming about a group that has the toughness of a street gang, but exists in an era before the brutality of crack cocaine and semi-automatic weapons. It plays into a nostalgic fantasy of the working class white ethnic Brooklyn of old. However, my own grandfather reminds me – between stories of how great Coney Island was in 1940 – that he left Brooklyn because it was full of poverty and violence, and he did not like poverty and violence. Those were things that caused him pain.

“Brooklyn Gang” is not a series about cool kids. It is a series about sad kids getting ready to go ahead and die. Many of these kids became heroin addicts, and many of them died very young. We know this because of the interviews that Davidson’s wife, Emily Haas Davidson, conducted with Bob Powers (aka “Bengie”), one of the gang members featured in the book, who eventually kicked drugs and went on to become a drug counselor. Even without this context of hindsight, death and tragedy are looming in the photographs themselves. In one photograph, a boy pulls a piece of dangling clothesline taught against his neck, and drops his head listlessly, as if he has been hanged. In another photograph, a boy balances his arched back on a pipe that spans the Hole, daring himself to drop into the precipice.

There is a part of me that wants to grab these kids and tell them that it will be all right. In my mind, I am speaking to them as a wise man in my late twenties, who has seen plenty of cool teenagers careen into addiction and death. My impulse is of course absurd, as the subjects would be (and in some cases are) in their sixties or seventies by now. But my relationship is not with the subjects as people in the world; it is with the subjects as kids in the photos. Every time I passed the photograph of the girl on the wall of the museum, I’d try to catch her eye. I wanted to talk to her. But if the camera didn’t catch the subject’s eye at the moment the picture was taken, the viewer will never be able to.

Davidson, however, dealt with the Jokers both as people and as photographic subjects. They existed, for him, first in the world, then in the lens, and then on paper. I imagine that the experience of being a documentary photographer is not unlike the experience that the poet John Keats had, while observing the public execution of three robbers in Venice. Keats wrote of the incident in a letter to his publisher, John Murray:

“I could hardly hold the opera-glass (I was close, but was determined to see, as one should see everything, once, with attention); the second and third (which shows how dreadfully soon things grow indifferent), I am ashamed to say, had no effect on me as a horror, though I would have saved them if I could.”

Books Mentioned:

Bruce Davidson, Brooklyn Gang (Santa Fe: Twin Palms Publishers, 1998)

TR820.5.N7 .D38 1988

Bruce Davidson, Black & White (Göttingen: Steidl, 2012)

Sidney Colvin, editor, Letters of John Keats to His Family And Friends (London: MacMillan and Co., 1925)